For the last 10 years or so, a team of scientists from the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee and the National Park Service has been helping to research the causes of botulism poisoning in birds along the shores of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore Park. Leading this team, Dr. Harvey Bootsma is a marine biologist and limnologist who has studied aquatic food webs and nutrient dynamics for over 20 years.

In this video, we interview Harvey about the work he and his team are doing to better understand how nutrients are cycling in Lake Michigan and the disruptive impacts of quagga mussels.

As well documented by NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab, two species of bivalve mollusks invaded Lake Michigan in the early 1990s. Zebra mussels were the first, but were quickly overrun and largely displaced by the more adaptable quagga mussels.

According to Harvey, quagga mussels now cover the bottom of most of Lake Michigan and are in the process of completely transforming the way nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus are cycling through the ecosystem. The change is both dramatic and on-going.

“It’s like playing a game and suddenly the rules have changed,” Harvey said. “So, managers are still trying to manage the lakes, but they’re not sure how the lakes are working right now. And the lakes are still changing from year to year. So, we’re trying to understand how they work while they’re changing … and that’s a tough thing to do.”

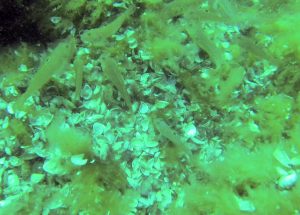

In the nearshore areas where Harvey and his team do most of their research, they find concentrations of quaggas at 5,000 to 10,000 per square meter.

Each mussel is able to filter ½ to 3 liters of water each day, consuming the plankton as they go. In short, they are clearing much of Lake Michigan of the very smallest plants that form the base of the food chain.

By consuming all this plankton, Harvey says, the quaggas are extracting the phosphorus from the open waters of Lake Michigan and recycling it in the nearshore benthic zones where bottom-growing algae can easily access it. As a result, quaggas are having a double impact on the ecology of the lake. They are increasing the clarity of the water, allowing more light to reach further down. And they are changing nutrient cycling.

“They’ve provided a perfect storm for benthic algae,” Harvey said. “They’ve taken the plankton nutrients from off shore in the water and transported them into the near shore area, concentrating the nutrients where the benthic algae is.”

The very rapid and extensive growth of algae can result in fouled beeches and clogged water intakes at power plants. And the organic rich, soup of dead algae can collect and provide the environments needed for the growth of bacteria, including the bacteria that releases the botulism toxin.

The impact of quaggas on Lake Michigan’s greater food web is also dramatic.

“The fishery as a whole is affected,” Harvey explains, “because you’ve reduced the amount of energy available for fish.”

In the interview, Harvey explains more about how the changes in the food web are impacting different species of fish such as salmon and trout, noting the role of another invasive species – a fish called the round goby.

For many of us, Lake Michigan is like a beautiful, vast freshwater sea. We can’t directly witness the changes taking place beneath that undulating blue surface. However, researchers like Harvey Bootsma’s team know that the lake’s ecosystem has fundamentally changed in just the last 15 years. And more change is underway.

[Note of Appreciation: We are grateful to the National Park Service (NPS) for letting us record activities on their service vessel. Thanks also to Dan Ray and Dave Schroeder, NPS staff members. Please note that the research efforts described above and in the video have been supported by the National Park Service, US EPA’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and the National Parks Conservation Association.]

3 thoughts on “Quaggas! Lake Michigan’s Ecosystem Disruptors”

Comments are closed.